Gallery Watch: Tura Oliveira at Geary on the Bowery

Captivated by the Brooklyn-based Emily Oliveira’s bold and saturated exhibition, I was lucky enough to speak to Geary’s gallery director Poppy DeltaDawn about “Red Velvet, Orange Crush.” The show in the gallery at 208 Bowery is packed with color, varying mediums and an innumerable amount of fascinating visualizations.

In an attempt to understand more about the artist’s process and broader practice, I reached out to Emily to ask about their research, studio time and exciting plans for the future.

As soon as you walk into Geary’s building, a painted orange and yellow, to blue and purple gradient covers the walls from floor to ceiling. Can you explain the intention behind transforming the gallery so boldly, and speak to how it affects the position of each of your works?

I wanted to give the viewer the feeling of standing on the precipice of something, possibly gazing at a light or a portal opening up onto another world. The colors in the gradient are also ones that are found together at sunset or sunrise, when our pupils are dilated and our eyes are starved for light, which heightens that sensory experience of color, of being at the threshold of something shifting and changing as you look at it.

One of my favorite things about the way we painted the space is that the gradient is built out of translucent layers of color — your eyes don’t stop at a flat color the way they do on most painted walls. Light passes through the layers of color and increases the feeling that the surfaces you’re looking at are in flux somehow.

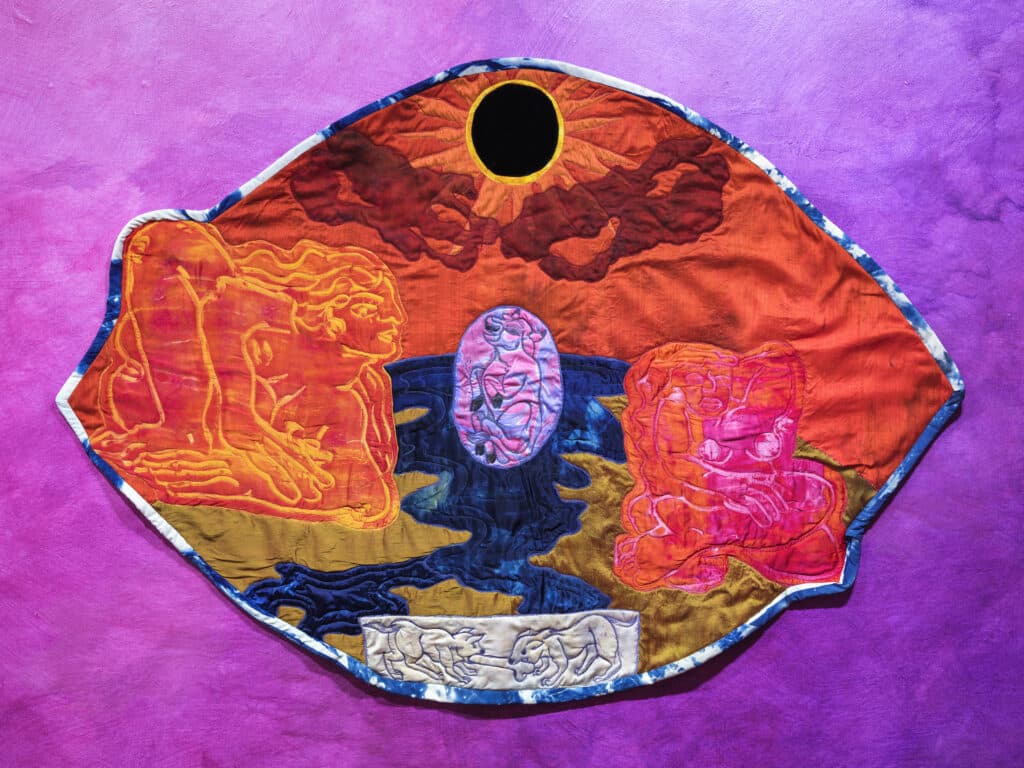

The quilts in your show are all different shapes and sizes, some ovular and some more circular. There is even one that appears more “eyelid” in shape. Is this aspect something you pre-plan in your studio, or is it something that occurs accidentally?

I started to play around with the shape of my quilts last spring, and since then I’ve realized that the impulse toward a curved or oblong shape has to do with making the viewer aware of the earth in space, and the picture plane of the quilt recalling vision more that it recalls an interior window or a framed painting. I tend to plan these shapes in my sketchbook, but I also try to respond to the materials as much as possible in the studio and do not try to make the fabric do things that it doesn’t want to do. I respond to the ways that it wants to pucker or drape.

Poppy, Geary’s gallery director, mentioned you have an interest and knowledge in the concept of hydromancy, a ritualistic practice that channels signs and warnings from water. Can you elaborate on how this idea inspired “Listening Bowl with Two Figures” (2021) and “Listening Bowl with Reclining Figure” (2021)?

I started making those small sculptures after a show last year when I wanted a little break from making quilts, and I thought about them immediately as vessels and tools for hydromancy. I think the idea of hydromancy relates to the gradient on the walls, and the water and the portals depicted in the quilts — a vision of something just beyond our reality appearing momentarily in a shifting liquid.

Speaking to notions of tradition and folklore, one of your quilts depicts the resurrection of an ox, which presumably references Brazil’s famous yearly celebration, Bumba Meu Boi, or perhaps the story behind it. Have you ever participated in its traditions outside of your immediate art-making?

I am interested in the idea of an ox shared by a community as a collectivist symbol, and its resurrection as a way of talking about the resiliency of leftist movements in Latin America. My connection to Bumba Meu Boi is primarily through heritage, the objects created for use in the performance, and an ongoing interest in the emancipatory potential of participatory performance.

Was it more human, animal or other that inspired the creation of “I am weak with much giving, I am weak with the desire to give more” (2022)? And, what soft or hard sculpture artists do you gravitate toward in your research?

I’m very influenced by practical effects (puppetry, miniatures, animatronics) in science fiction and horror movies from the 1970s-90s, and particularly that their general disappearance from film has nothing to do with obsolescence and everything to do with labor (workers in CGI are not unionized but fabricators and designers of practical effects are).

The film influences on this particular sculpture are “Species,” “Alien” and “Jumanji,” with the horror of the first two based in the monstrous feminine, and the last one the colonial trope of the “hungry jungle” — two concepts pretty near and dear to my practice.

So, as a roundabout way of answering your question, I’m interested in taking the horror associated from the blurring of boundaries between the “human, animal, or other” and turning it inside out, and hopefully into something tantalizing, erotic and post-human.

The writer for your catalog, Kyle Dacuyan, claims that visual mythologies, ecological considerations and the cosmos are all areas that “Red Velvet, Orange Crush” explore. They also poetically write that the work rides on reverie. Do you feel as though all of your work deals with sentiments that Dacuyan describes? And, will you adopt this vernacular moving forward with your artistic practice?

I’ve been working with interlocking mythological and science fiction narratives in my work for several years now, and the work is invariably informed by present ecological collapse. The cosmos comes into play in a way that relates to your question about the shape of the textiles — trying to call attention to our own subjectivity and that we are caught between two parentheses: a living earth and an infinite cosmos.

You’ve used processes such as hand-dying, sewing, stitching and cyanotype. You have also used silks, velvets, linens and sequins, to name a few of your materials. While making the work for the show, what process or materials did you struggle with the most, and how long — roughly — did “Red Velvet, Orange Crush” take until it was ready to hang as a show?

All of the work for the show came together in a little less than a year. I think I continue to struggle the most with time and the time-consuming process of appliqué and quilting. Hand dyeing is a fast and loose process that requires a lot of preparation and a lot of steps, but I really enjoy all of the different processes that my studio practice allows me to engage in. I think if I was only doing one process every day I would not feel as excited to go to the studio.

Is there anything extremely important to know before a viewer sees your work for the first time in person?

I think other than knowing that the works in the show are all handmade textiles (with the exception of the two small paper pulp sculptures on the mantle), I ideally would want the viewer to have an unmediated sensory experience of the work! I also think the work and the painting on the wall are particularly beautiful in the daytime, with sunlight coming in from the windows.

What do you hope to focus on after you have finished your studies? What do you have in store exhibition/show wise?

After I graduate in 2023, I’m going to be in Rome for a year at the British School at Rome, which I’m really thankful and excited for. Right now I have a mural that’s at the Lena Horne Bandshell in Prospect Park until early May, and in the fall, I’m going to have another solo exhibition at LaMama Galleria that’s opening in September 2022.

I’ll also have my thesis exhibition sometime next year, both in New Haven and at a space in New York. I’m excited to continue exploring textiles and expanding my practice. I also want to continue exploring videos and performances that have been set aside for a while since I’ve been in school.