Elusive Cats Abound in Catherine Haggarty’s ‘Living’ Interiors

Recalling a memory is much like a game of telephone. The details change, confidence in narrative waivers, and the overall meaning slowly evolves. Over the last two years, as the world was forced inside, the external elements that helped form memories disappeared and all that was left were our interior spaces. “Living” meant living inside. In Catherine Haggarty’s first solo show with Geary Contemporary, aptly titled Living, she explores this condition of the previous two years in paintings of intimate interior scenes with distorted perspective and layers of references to art history. Haggarty’s paintings, made of collaged materials including oil stick, acrylic, wax crayon, and airbrush, often depict figures who are almost always sleeping, sometimes alone, sometimes with other people and cats. Many of her paintings are bathed in dreamy hues of blue and purple. Motifs repeat, morph, and move across the room. Haggarty asks the viewer to question their own memory and sense of logic and to reflect on the people, spaces, and things that comprised our lives for two long years.

Recalling a memory is much like a game of telephone. The details change, confidence in narrative waivers, and the overall meaning slowly evolves. Over the last two years, as the world was forced inside, the external elements that helped form memories disappeared and all that was left were our interior spaces. “Living” meant living inside. In Catherine Haggarty’s first solo show with Geary Contemporary, aptly titled Living, she explores this condition of the previous two years in paintings of intimate interior scenes with distorted perspective and layers of references to art history. Haggarty’s paintings, made of collaged materials including oil stick, acrylic, wax crayon, and airbrush, often depict figures who are almost always sleeping, sometimes alone, sometimes with other people and cats. Many of her paintings are bathed in dreamy hues of blue and purple. Motifs repeat, morph, and move across the room. Haggarty asks the viewer to question their own memory and sense of logic and to reflect on the people, spaces, and things that comprised our lives for two long years.

Catherine Haggarty, “Day Time Nap.” Oil stick, acrylic, and airbrush on canvas, 2022. 20 x 16 in. Photograph courtesy of Geary Contemporary.

To explore her life during lockdown, Haggarty chose mainly to depict the interior of her bedroom with figures sleeping as the light of the day changes around them. The viewer is afforded an intimate look into these private moments. In Day Time Nap, a figure lies diagonally across a disheveled bed, suggesting a restless slumber. The sleeper has settled with their head just off the edge, as if still tossing to find the perfect spot. Fractured, washy light bathes the room.

The perspective of Day Time Nap with the viewer looking from the foot of the bed is used in most of the bedroom scenes. The lighting, occupants, and colors of each work change to the point where it becomes unclear whether the same room is represented, yet familiar objects cycle throughout. These subtly contradicting senses of familiarity and uncertainty cause the viewer to pause and question their own memory to decide whether they’ve seen each image already or not. After two years of intermittent periods of lockdown and isolation, this sense of confused repetition, in particular of an interior space, is undeniably familiar.

Throughout her work, Haggarty plays with light, shadow, and perspective to convey a range of feelings from dramatic and overwhelming to calm and ethereal. In Kitten Hunting, an ominous, elongated shadow of a cat streams across a pink curtain like Batman’s signal beaming into the sky. The cat appears to be looking in from a window, perhaps sneaking over the viewer’s shoulder.

A similar use of light and shadows appears in Too Many Ideas, in which the outline of a head and torso is shown filled with overlapping images. The dreamy composition nods to the pseudoscience of phrenology, as well as the work of Surrealists. Some of the show’s recurring motifs are depicted in the layered images inside the head, including pyramids and a sleeping figure. Little context is provided for the recurring images. The pyramids seen in Too Many Ideas appear on various objects throughout Haggarty’s interiors from lampshades to rugs. Like a game of “I spy,” the viewer is invited to pick out these moments of repetition, yet there is no final meaning to be parsed. The viewer is denied the satisfaction of creating a pattern or logic. Instead, the works are purposefully vague and elusive, like visual representations of a memory that changes slightly every time it is recalled. Both the title of the work and the piled imagery allude to being overwhelmed, yet the work bears no signs of stress. Rather, the figure appears to methodically layer its ideas and resolves itself to simply having too many. The work is a welcome invitation to let the mind wander and embrace the feeling of being burdened.

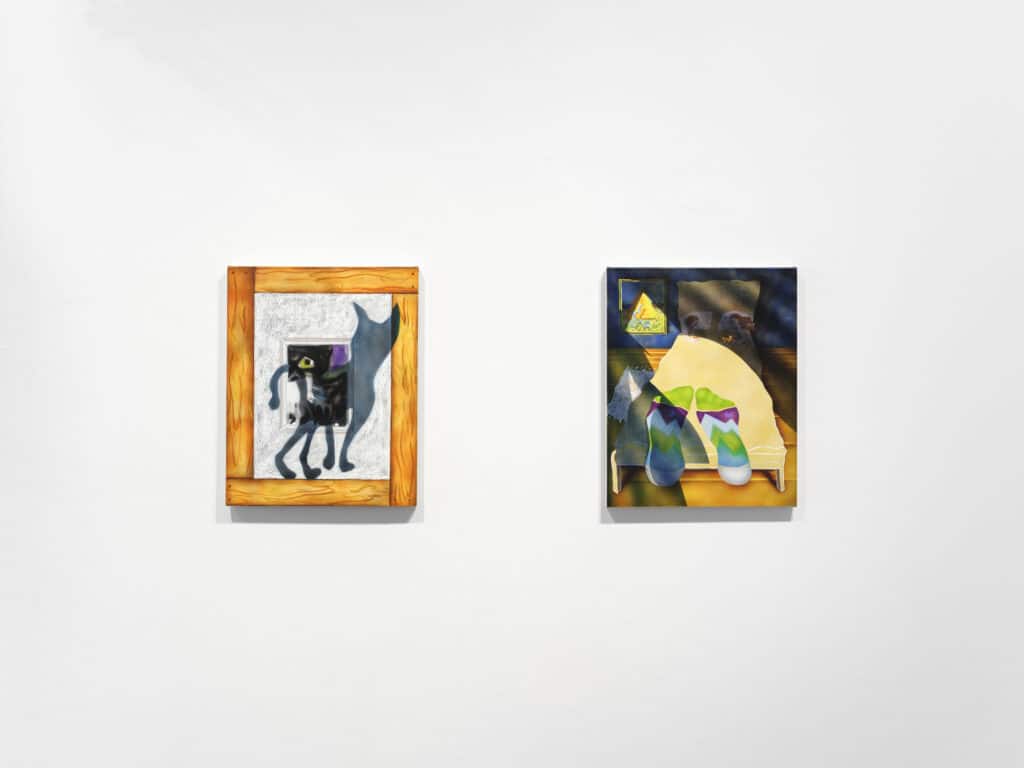

In addition to strong references to Surrealism, Haggarty also pays homage to Jasper Johns, seen, for example, with the natural wood frame she has painted surrounding a portrait of a cat in For Penguin. Johns often painted a border or frame around his compositions, and wood grain appears in many details throughout his work. The frame in Haggarty’s painting surrounds a feral cat named Penguin who peeks out from behind a mysterious feline silhouette, perhaps her shadow, or perhaps one of the male cats that the artist said liked to hunt poor Penguin. The work is both heartwarming and foreboding. An homage to the sweet, innocent black cat who became the artist’s companion during lockdown, there is also a sense of fear in her eyes as she peers out at the looming shadow.

The subtle reference to Johns in Haggarty’s faux frame is just one of many moments in which she pays homage to the artist, as well as other greats of art history. Hints of Johns appear in Haggarty’s color choices, as well as in the two artists’ mutual exploration of dreams, Surrealist imagery, and illusion, seen in particular in Johns’ works from the 1980s and 90s. Johns’ recent retrospective at the Whitney, Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, included an untitled painting from 1990 of a purple sheet folded as if neatly tucked in on a bed, yet clothespins suggest the sheet is floating, much like the curtain hanging in Haggarty’s Kitten Hunting.

Purple often appears in subtle hints throughout Johns’ work. Haggarty also seems partial to purple. In Babylon, she has painted a dreamy figure lounging on a bed in the background. In the foreground lies a carpet bearing a depiction of the Ishtar Gate, one of the gates of the ancient city of Babylon. Inside the gate, Haggarty has painted even more pyramids. A purple, ethereal hue washes over the scene, parted in the center as if being pulled to the side. Haggarty’s piece immediately recalled the purple bedsheet floating in Johns’ painting.

While many works in the genre verge on depressive, Haggarty’s isolation paintings are triumphant. They recognize our resilience and embrace our collective groundhogs day syndrome, the feeling of reliving the same day over and over again. They are further triumphant in their celebration of the small things that make up our lives–the relationships, the pets, the possessions that became our companions for two years. Haggarty successfully captures the condition of interiority that defined our lives and paints a memorial to her own experience of what it means to be “living”.